I spend so much of my time shielding myself from the carnage being perpetrated by my sons playing Halo 3 just outside the kitchen. But last night my 16-year-old and I went to see the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Julius Caesar, and we came home feeling almost as blood-soaked as the Roman senators. Shakespeare's Elizabethan audiences loved watching the actors beat each other bloody, and violence can still enthrall and terrify even those of us who usually try to avoid it.

I spend so much of my time shielding myself from the carnage being perpetrated by my sons playing Halo 3 just outside the kitchen. But last night my 16-year-old and I went to see the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Julius Caesar, and we came home feeling almost as blood-soaked as the Roman senators. Shakespeare's Elizabethan audiences loved watching the actors beat each other bloody, and violence can still enthrall and terrify even those of us who usually try to avoid it.

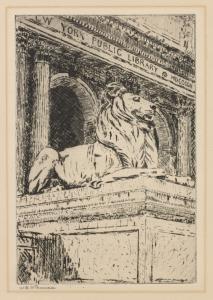

When the senators killed Caesar, it was a gruesome, intricately choreographed mess. From our seats in the balcony of the RSC’s facsimile of the Globe Theater, set up in the cavernous and beautiful Park Avenue Armory, we could see the anguish, fear and anger in the eyes of everyone, murderer and murdered alike. This was not video-game gore, distant and clinical, where your character can die but always returns. This was awful, personal, and final. After Caesar utters his famous “Et tu, Brute?”, Brutus embraces his old friend while thrusting in his dagger for the final cut, and Caesar dies in his arms.

The murder scene made both my son and me shudder. Later he said “Did you know, mom, that the word brutal comes from Brutus?” I hadn’t, but after watching this performance, the derivation made perfect sense.

Here you can watch the scene just before the carnage, when Caesar’s wife Calpurnia pleads with him to stay home that day, and also the scene just after the murder, when Mark Antony, red up to the elbows in Caesar’s blood, laments his friend’s death and vows to “let slip the dogs of war.”

In Antony’s public speech, made “to bury Caesar, not to praise him,” the soldier says he’s no great orator like Brutus. Yet he cunningly turns the tide of public emotion with his sarcastic words against the murderers.

The way Antony manipulates the crowd by subverting their expectations of him made me think of the new movie The Guard, out today in New York. It's a dark, hilarious film whose main character, Gerry Boyle, brilliantly played by Brendan Gleeson, is also not what he seems. On the surface he’s a big, lumbering, bored, racist, and not very bright cop in a remote seaside town on the coast of Ireland. But as his unlikely partner, a black FBI agent played by Don Cheadle, says, “I don’t know if you’re really fuckin’ dumb, or if you’re really fuckin’ smart!” Both Antony and Boyle understand the power of playing with people’s expectations, and revel in messing with their unsuspecting audiences.

The way Antony manipulates the crowd by subverting their expectations of him made me think of the new movie The Guard, out today in New York. It's a dark, hilarious film whose main character, Gerry Boyle, brilliantly played by Brendan Gleeson, is also not what he seems. On the surface he’s a big, lumbering, bored, racist, and not very bright cop in a remote seaside town on the coast of Ireland. But as his unlikely partner, a black FBI agent played by Don Cheadle, says, “I don’t know if you’re really fuckin’ dumb, or if you’re really fuckin’ smart!” Both Antony and Boyle understand the power of playing with people’s expectations, and revel in messing with their unsuspecting audiences.

I had the opportunity to interview Don Cheadle on Monday about the unexpected pleasures and challenges of The Guard. He was open and generous, and talked about the pleasures of playing a character who mostly reacts, rather than acts, and about his love of jazz and how music plays a part in his performance as an actor. Here’s the conversation: